Assessing Oral Health Literacy and Oral Behavior among 18-74 years Old Patients in Imphal East District, Manipur

by Shamilah Khanam1*, Deborah Gonmei2, Eremba Khundrakpam2

1Department of Public Health Dentistry, Dental College JNIMS

2Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Dental College, JNIMS

*Corresponding author: Shamilah Khanam, Department of Public Health Dentistry, JNIMS, Dental College, Imphal East District-795005, Manipur, India

Received Date: 08 August, 2023

Accepted Date: 14 August, 2023

Published Date: 18 August, 2023

Citation: Khanam S, Gonmei D, Khundrakpam E (2023) Assessing Oral Health Literacy and Oral Behavior among 18-74 years Old Patients in Imphal East District, Manipur. J Community Med Public Health 7: 353. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100353

Abstract

Introduction: Literacy and attitude influence a patient’s oral behavior and compliance with the instruction and advice provided by the dentist. So far, only a few studies have been conducted in the northeastern states of India on oral health literacy. Objective: The objectives were to assess Oral Health Literacy (OHL) among adult OPD patients at the Dental College, JNIMS, Manipur, and its relationship with education level and Oral behavior, respectively. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 225 adult patients attending the Dental College using a validated questionnaire. Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry (REALD30) assessed OHL. The collected data were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS 24. Pearson's chi-square test assesses the association between various other parameters and REALD-30. One-way ANOVA evaluated the relation between REALD30 (categorized-high, moderate, and low) and time. Chi-square tests the association of Oral Behavior questionnaire items with oral health literacy scores. Results: The OHL was significantly related to the patient's age, marital status, and level of education, with the literacy score higher in females than in males. Significant associations were found between REALD-30 score and oral behavior such as brushing, rinsing after meals, other oral hygiene aids, changing brush, using appropriate toothpaste, etc. Conclusion: Oral Health Literacy is significantly related to patients' age, marital status, and education, with higher scores in females than males. Limitation: The study participants were confined to a single institution, requiring further studies on a larger population.

Keywords: Dentist; Oral Health Literacy; Oral Behavior; Patients; REALD-30

Introduction

An individual’s health literacy is the ability to perceive health depending upon education, and knowledge adequacy attributes that are affected by the culture, language, way of life, and health-related practices of people in diverse environments [1,2].

Health literacy strongly predicts an individual’s health, health behavior, and health outcomes [1]. A person with limited oral health literacy has been reported to be at a higher risk of oral diseases and associated problems [2]. Oral Health Literacy (OHL) is vital for a dentist to ascertain the patient’s literacy level before any procedure and then treat a patient according to the level of understanding of the patient. Only a few studies, so far, have been conducted on Oral Health Literacy (OHL) and Oral Behaviors along with the level of education among the people of Manipur, India.

The study aims to assess Oral Health Literacy (OHL) by using the validated instrument Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Dentistry (REALD-30) and Oral Behaviors among adult (aged 18-74 years) patients attending the dental OPD in Dental College, Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences (JNIMS), Porompat in the State of Manipur, India.

Objectives

- Assess oral health literacy among adults visiting the OPD dental college, JNIMS, Imphal East, Manipur.

- Assess the relationship between Oral Health Literacy (OHL) and education level.

- Assess the relationship between Oral Health Literacy (OHL) and Oral Behavior.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from February 2022 to June 2022 among 225 patients for an initial consultation at the Out Patient Department in Dental College, JNIMS, Porompat, Imphal East, Manipur. A pilot study was conducted on a sample of 50 participants in which 88% presented with high oral health literacy. Based on this, the sample size was estimated to be 225 participants. While selecting only those participants who could understand the Basic English language were selected. The participants were young adults and middle–and old senior citizens who came to the college for various dental treatments. The information was read to them in the local language (if required). If they had any doubt or difficulty understanding the information provided, the investigator gave a proper explanation until they understood thoroughly. The study process started only when it was convinced that the participants fully understood the instruction. The study was conducted with the prior approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal-795005 (ECR/1333/Inst/MN/2020).

Inclusion Criteria

- Participants who understand the Basic English language.

- Participants should be >18 years of age <74 years of age.

- Participants without cognitive impairment, without vision or hearing problems.

- Participants without obvious signs of drug /alcohol intoxication.

Exclusion Criteria

- Participants with psychiatric disorders and other severe systemic illnesses.

- Participants who are not willing to participate in the study.

- Minors, pregnant women, neonates, prisoners, etc.

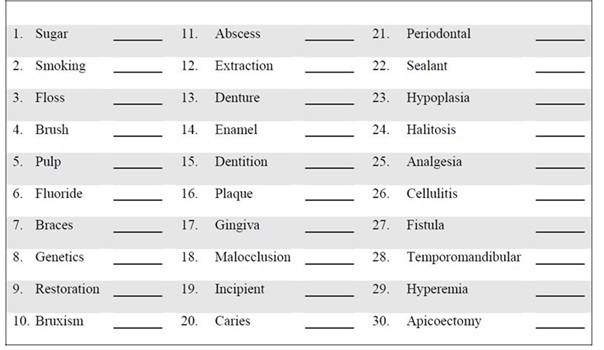

All study participants gave their written informed consent. The participants consent was obtained voluntarily after a brief conversation and explanation about the study. The Oral Health Literacy Assessment was done using REALD-30 (Figure 1), a word recognition instrument with 30 dental-related words arranged in order of increasing difficulty [4]. Timers were set for each participant, with zero points if it is incorrect. The participants read the words loudly to the interviewer and were asked to skip the word if they did not know; each participant got one point for the correct word (within 1 minute). The REALD30 score was categorized as high, moderate, and low.

Figure 1: REALD-30 Assessment Form.

In addition to the above, each participant completed a questionnaire regarding Oral Behavior with 13 questions. The participants were asked to mark only one response to each question. Socio-demographic data were also taken along with the questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS (version 24.0). Pearson’s chi-square ( χ2) test was used to assess the association between various other parameters and REALD-30. Significance level was set at 0.05. One-way ANOVA was used to assess the relation between REALD30 (categorized-high, moderate, and low) and time (continuous variable). The association of Oral Behavior questionnaire items with oral health literacy scores is analyzed by Chi-square test.

Results

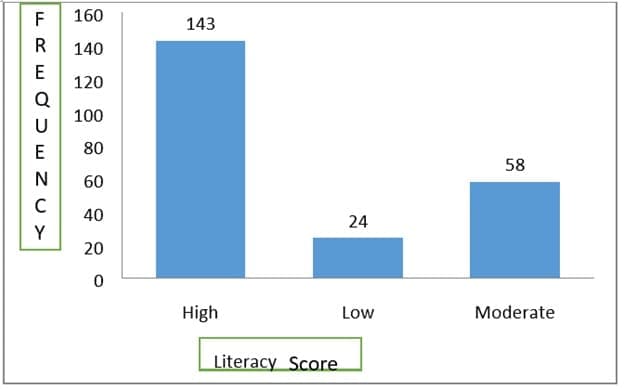

A sample of participants (N=225) was recruited from patients presenting for an initial consultation at a Dental OPD JNIMS Dental College, Porompat. Of the 225 participants, 137 (60.9%) were males, and 88 (39.1%) were females. Most patients visiting the Dental College hospital, JNIMS, spoke Manipuri as an official language. Among the different age groups, the maximum number of participants (n=123, 54.7%) were found to be of 18-30 years of age and 66 years (n=11, 4.9%) & above. Among the study participants, 102 students (45.3%), followed by unemployment 51 (22.7%), 29 (12.9%) were shop owners, and 20 farmers (8.9%) were professionals. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Based on the interquartile range of Oral Health Literacy scores, the participants were divided and found that 143 (63.6%), 58 (25.8%), and 24 (10.7%) had high, moderate, and low scores with a mean score of 24.99±10.07 (Figure 2). Furthermore, the relationship between age, gender, marital status, education status, and REALD30 has been presented in Table 2.

|

Variables |

Participants (%) N=225 |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

88 (39.1%) |

|

Female |

137 (60.9%) |

|

|

Age |

18- 30 |

123(54.7%) |

|

31-45 |

52(23.1%) |

|

|

46-55 |

21(9.3%) |

|

|

56- 65 |

18(8.0%) |

|

|

≥66 |

11(4.9%) |

|

|

Marital status |

Married |

108 (48.0%) |

|

Unmarried |

117 (52.0%) |

|

|

Education |

Middle school certificate |

3.6% (8) |

|

High school certificate |

20.0% (45) |

|

|

Intermediate |

12.0% (27) |

|

|

Graduate and postgraduate |

63.6% (143) |

|

|

Professional Degree |

0.9% (2) |

|

|

Occupation |

Student |

45.3% (102) |

|

Unemployed |

22.7% (51) |

|

|

Unskilled |

1.3% (3) |

|

|

Semi-skilled |

0.9% (2) |

|

|

Skilled |

5.3% (12) |

|

|

Shop owners, farmers |

12.9% (29) |

|

|

Semi-professional |

2.7% (6) |

|

|

Professional |

8.9% (20) |

|

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

Figure 2: Distribution of OHL scores among study participants.

|

Oral Health Literacy Score (REALD-30) |

||||||

|

High |

Moderate |

Low |

Chi-square |

Sig |

||

|

Age (in years) |

18- 30 |

49.2% |

31.5% |

19.4% |

33.61 |

0.00 |

|

31-45 |

76.5% |

23.5% |

0.0 % |

|||

|

46-55 |

90.5% |

9.5% |

0.0 % |

|||

|

56- 65 |

83.3% |

16.7% |

0.0 % |

|||

|

≥66 |

81.8% |

18.2% |

0.0 % |

|||

|

Gender |

Female |

61.3% |

28.5% |

10.2% |

1.326 |

0.51 |

|

Male |

67.0% |

21.6% |

11.4% |

|||

|

Marital status |

Unmarried |

45.3% |

34.2% |

20.5% |

41.62 |

0.00 |

|

Married |

83.3% |

16.7% |

0.0% |

|||

|

Education status |

Middle school |

83.2% |

0.0 |

16.8% |

41.66 |

0.00 |

|

High school |

88.9% |

11.1% |

0.0 |

|||

|

Intermediate |

88.9% |

11.1% |

0.0 |

|||

|

Graduate & PG |

48.3% |

35.0% |

0.0 |

|||

|

Professional |

0.0 |

100.0% |

0.0 |

|||

Table 2: Relationship of age, gender, marital status, and education status with REALD-30.

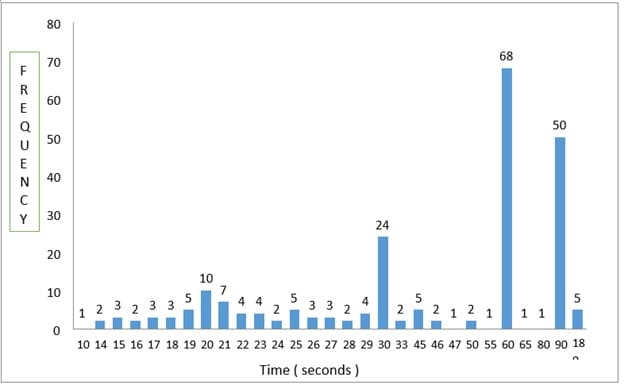

The OHL was significantly related to the age, marital status, and level of education of patients. Overall, the literacy score is higher in females, 61.3%, than in males and was found to be non-significant (p=0.51). Most of the participants took 60 seconds 68 (30.2%) to answer the literacy score word with a mean time of (54.56±32.1 seconds) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Time taken to answer the literacy score words.

Oral Health Behaviors among Study Participants

The present study revealed that most of the participants with the highest oral health literacy had favorable oral behaviors, which was found to be statistically significant (p=0.05) (Table 3). The majority of participants, 76.9%, brushed their teeth once a day and 71.4% changed their brush every 3-6 months, with 76.2% used non-fluoridated toothpaste. Of most participants, 68.5% brush their teeth for over 2 minutes. Almost all of the participants, 95.2%, do not know about rinsing after meals, and more than half of the participants, 66.7%, have not used oral hygiene aids, 63.7% and (68.2%) used toothpaste and tongue cleaner as cleaning aids.

|

Response |

High OHL (%) |

Moderate OHL (%) |

Low OHL (%) |

Chi-square |

Sig (p-value) |

|

1. Frequency of brushing |

|||||

|

Once |

76.9% |

19.4% |

3.7 % |

19.41 |

0.0 |

|

Twice or more |

50.9% |

31.6% |

17.5 % |

||

|

Once a week |

0.0% |

33.3% |

66.7 % |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

||

|

2. Cleaning Aids |

|||||

|

Toothpaste |

63.7% |

25.6% |

10.8 % |

0.733 |

0.69 |

|

Toothpowder |

50.0% |

50.0% |

0.0% |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

||

|

3. Rinsing after meals |

|||||

|

Yes |

58.5% |

28.8% |

12.7 % |

12.64 |

0.04 |

|

No |

75.0% |

0.0% |

25.0 % |

||

|

Sometimes |

62.2% |

28.0% |

9.8% |

||

|

Do not know |

95.2% |

4.8% |

0.0 % |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

||

|

4. Oral hygiene aids |

|||||

|

Dental floss |

18.8% |

37.5% |

43.8 % |

28.15 |

0.0 |

|

Tongue cleaner |

68.2% |

25.0% |

6.8 % |

||

|

Mouthwash |

50.0% |

25.0% |

25.0% |

||

|

None |

66.7% |

23.8% |

9.5 % |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

||

|

5. Time of changing brush |

|||||

|

Once a month |

71.4% |

28.6% |

0.0 % |

34.55 |

0.00 |

|

3-6 month |

88.9% |

30.2% |

19.8 % |

||

|

6-12 month |

60.0% |

35.0% |

5.0 % |

||

|

Change only when it becomes unusable |

0.0% |

11.1% |

0.0 % |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

||

|

6. Type of toothpaste |

|||||

|

Fluoridated |

36.5% |

33.3% |

30.2 % |

53.23 |

0.00 |

|

Non-fluoridated |

76.2% |

20.0% |

40.0 % |

||

|

Herbal |

64.3% |

21.4% |

14.3% |

||

|

Do not know |

0.0% |

23.1% |

0.7 % |

||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

|

7. Time of brushing |

||||||||||

|

Less than 1 min |

44.4% |

44.4% |

11.1 % |

21.73 |

0.00 |

|||||

|

1-2 min |

57.7% |

28.2% |

14.1 % |

|||||||

|

2min |

0.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

|||||||

|

More than 2 min |

68.5% |

23.8% |

7.7 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

|

8. Dental visiting pattern |

||||||||||

|

First Visit |

78.1% |

21.9% |

0.0 % |

35.03 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

Once in 6 months |

44.4% |

33.3% |

22.2 % |

|||||||

|

When there is a problem |

48.7% |

31.9% |

19.5% |

|||||||

|

Never |

89.7% |

10.3% |

0.0 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.4% |

25.9% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

|

9. Reason for last dental visit |

||||||||||

|

Restoration /pain |

63.5% |

25.0% |

11.5 % |

6.17 |

0.40 |

|||||

|

Oral prophylaxis |

42.9% |

42.9% |

14.3 % |

|||||||

|

Extraction/minor surgery |

65.7% |

25.7% |

8.6% |

|||||||

|

Other |

68.4% |

21.1% |

10.3 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

62.5% |

26.4% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

|

10. Self-examination of the oral cavity |

||||||||||

|

Yes |

57.7% |

28.6% |

13.7% |

16.39 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

No |

85.1% |

14.9% |

0.0 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.6% |

26.0% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

|

11. Reason for self–checking mouth in the mirror |

||||||||||

|

Painful teeth |

65.2% |

32.6% |

2.2 % |

17.62 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

Food lodgement |

60.8% |

17.6% |

21.6 % |

|||||||

|

Mouth sores |

75.0% |

0.0% |

25.0% |

|||||||

|

Routinely |

52.3% |

38.5% |

9.2 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.3% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

|

12. Last time of oral prophylaxis |

||||||||||

|

One month back |

20.0% |

40.0% |

40.0 % |

49.16 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

Six months back |

27.8% |

38.9% |

33.3 % |

|||||||

|

One year |

42.9% |

30.6% |

26.5% |

|||||||

|

None /never |

76.4% |

21.6% |

2.0 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.9 % |

|||||||

|

13. Self-rating oral health |

||||||||||

|

Fair |

41.4% |

34.5% |

24.1 % |

31.06 |

0.0 |

|||||

|

Good |

82.9% |

30.1% |

17.2 % |

|||||||

|

Very good |

52.1% |

36.4% |

0.0% |

|||||||

|

Poor |

63.6% |

16.1% |

1.1 % |

|||||||

|

Total |

63.6% |

25.8% |

10.7 % |

|||||||

Table 3: Relation of oral health behaviors and REALD-30 scores (high, moderate, low) among study participants.

Most participants, 89.7%, never visited the dentist often, and more than half of the participants, 65.7%, had reasons for their last dental visits being for extraction or minor surgery. 85.1% of participants do not have a habit of self-examination. Mouth sores 75.0% were the reason for self–checking mouth in the mirror for most of the participants. 76.4% of participants do not have a professional cleaning (oral prophylaxis), and most rated their oral health score as good, 82.99%.

Discussion

The success of dental treatment depends on the patients and the dental care rendered by the dentist. Literacy and knowledge influence a patient’s oral behavior and compliance with the instruction and advice provided by the dentist.

The present study was conducted to assess Oral Health Literacy among adults visiting the OPD Dental College, JNIMS, Imphal East, Manipur. In this study, we used a word recognition instrument, the REALD-30. This instrument needs to consider whether the individual comprehends the dental words [3,6] to assess oral health literacy since previous studies demonstrated a strong correlation between general reading ability and reading comprehension, a higher-order skill [7]. Regarding the distribution of oral health literacy scores, it was found that 143 (63.6%)study participants presented with high oral health literacy scores with a mean of 24.99±10.07which is almost similar to the study REALD score of 23.9±1.29 by Jones, et al. [7] where it was among patients attending a dental clinic. In contrast, the present study was done among JNIMS OPD Dental college patients during dental visits. The oral health literacy scores were higher in females (61.3%) than in males. This indicates that gender influences oral health literacy but was statistically non-significant (p=0.51). This result also complies with other studies Al-Sharbatti, et al. and Sadek [4] and Braimoh, et al., and Owoturo [5], which observed that gender influence literacy and non–significantly.

When educational qualifications were compared with mean health literacy scores in studies by Jones, et al. [7]these studies reported that education is vital in determining oral health literacy.

In the present study, OHL was significantly related to the participant’s education level. Participants were asked to read out REALD-30 words loudly (within 1 minute), and timers were set for each participant, and most of the participants took 60 seconds 68 (30.2%) to answer the literacy score REALD-30 words with a mean time of (54.56±32.1 seconds).

In the present study, most of the study participants (76.9%) brushed their teeth once daily and used toothpaste (63.7%) and tongue cleaner as their cleaning aids (63.2%). Most of the study participants were not aware of fluoridated toothpaste, of which the majority (68.5%) took more than 2 minutes to brush their teeth, as of 88.9% of participants changed their brush within 3-6 months and observed that higher Oral health literacy scores were found to be highly significant. In the study reported by Sistani, et al. [8], Oral health literacy and oral health behavior were also observed the same.

Although using oral health services is based on individual needs and risk factors, [11] regular dental visits can be considered a part of preventive oral health intervention [10,11]. It was observed that a higher oral health literacy score visited the dentist more often than in other groups, and the difference was significant. Similarly, Sistani, et al. [8] found a significant association between OHL scores and dental visits and the use of dental services.

Most dental visits are aimed at the immediate relief of pain. Most patients in India often visit a dentist at the later stages of dental disease when symptoms such as pain and extreme discomfort appear rather than earlier [12]. The usual assumption or belief that there was no need to visit a dentist unless the pain was present was reported by Al-Shammari KF, et al. [13]. The present study reveals, most of the participants visited the dentist, mainly for pain/restoration and least for oral prophylaxis. A study conducted by Tanikonda, et al. [12] stated that most people received dental restoration (46%) followed by the least (26%) oral prophylaxis and dental pain which adversely affected quality of life, normal functioning, and daily living of people.

Participants with higher oral health literacy had a habit of self-examination routinely, and the reason for self-examination was due to food lodgment, painful teeth, mouth soreness. Similar results were also reported in the study conducted by Khajuria S, et al. [14]. In the present study, most of the participants rated their oral health score as good, followed by very good in the self- rating oral health by participants belonging to high oral health literacy score and were found to be significant and is equivalent to study conducted by Jamieson LM, et al. [15].

Conclusion

The study reveals that most of the participants were 18- 30 years of age, and OHL scores were found with a higher mean REALD score of 24.99±10.07. Literacy scores are higher in females than males. To answer the literacy score (REALD-30) words, most of the participants took 60 seconds 68 (30.2%) with a mean time of (54.56±32.1 seconds). In this study, most participants with the highest oral health literacy had good oral health behaviors. The study’s objective is to promote oral health, prevention of oral diseases, and development of a healthy oral cavity to improve quality of life and cost reduction for achieving health and well-being and attaining oral health literacy among the people of Manipur. There is a mutual benefit in the study. The study may empower the participants to act in one healthcare. The individual could be a well-informed agent to spread healthcare literacy among citizens.

References

- Berkman ND, Davis TC, Mc Cormack L (2010) Health literacy: what is it? J Health Commun 15: 9-19.

- Horowitz AM Kleinman DV (2012) Oral health literacy: a pathway to reducing oral health disparities in Maryland. J Public Health Dent 72: S26-S30.

- Lee JY, Rozier RG, Lee SY, Bender D, Ruiz RE (2007) Development of a word recognition instrument to test health literacy in dentistry: The REALD-30: A brief communication. J Public Health Dent 67: 94-98.

- Al-Sharbatti S, Sadek M (2014) Oral Health Knowledge, Attitudes and practices of the elderly in Ajman UAE. Gulf Med J 3: S152-S164.

- Braimoh OB, Owuturo EO (2016) Oral health Knowledge, attitude and behavior of medical, pharmacy and nursing students at the University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. J Oral Res Rev 8: 66-71.

- Srivastava S, Acharya S, Singhal DK, Dutta A, Kalra K, et al. (2020) Oral health literacy and its relationship with the level of education and self–efficacy among patients attending a dental rural outreached clinic in India. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development 11: 193886.

- Jones M, Lee JY, Rozier RG (2007) Oral Health Literacy among adult patients seeking dental care. J Am Dent Assoc 138: 1199-1208.

- Sistani MMN, Virtanen J, Yazdani R, Murtomaa H (2017) Association of oral health behavior and the use of dental services with oral health literacy among adults in Tehran, Iran. Eur J Dent 11: 162-167.

- Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, Rozier RG, Vann Jr WF, et al. (2012) The Relationship of Oral Health Literacy and Self-Efficacy with Oral Health Status and Dental Neglect. Am J Public Health 102: 923-929.

- Patel S, BayRC, Glick M (2010) A systematic review of dental recall intervals and incidence of dental caries. J Am Dent Assoc 141: 527-539.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2013) Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent 35: E148-E156.

- Rambabu T, Koneru S (2018) Reasons for use and nonuse of dental services among people visiting a dental hospital in urban India: A descriptive study. J Edcu Health Promot 7: 99.

- Al-Shammari KF, Al-Ansari JM, Al-Khabbaz AK, Honkala S (2007) Barriers to seeking preventive dental care by Kuwaiti adults. Med Princ Pract 16: 413-419.

- Khajuria S, Koul M, Khajuria A (2019) Association between oral health behavior and oral health literacy among college students. International Journal of Applied Dental Sciences 5: 86-90.

- Jamieson LM, Divaris K, Parker EJ, Lee JY (2013) Oral health literacy comparisons between indigenous Australians and American Indians. Community Dent Health 30: 52-57.

Research Article

Research Article